Friday, February 29, 2008

The Sixth Annual Fractal Fair

Come see the creative projects of 60 students at the sixth annual Fractal Fair on Friday, February 29! It will be held in the High School Library (including the Library Computer Lab) from 9:15 to 1:15, which is most of Blocks B, D, and H. Learn about models of 3-D fractals, the creation of special effects in movies, fractals in science, fractal music (with original compositions!), the fractal structure of plants, fractal movies, the fractal dimension of coastlines, the creation of forests, a card game with fractal images, and other applications of fractals in mathematics, science, and art.The students’ projects definitely met expectations, in terms of both creativity and mathematics. Almost all of the participants had had to learn material that was new to them, in order to extend what they learned in class, and all of them had to organize and present their knowledge in a manner that would make sense to adults and students who knew nothing about fractals. This year, for whatever reason, there was very little about the Mandelbrot Set; most of the projects investigated fascinating connections with chemistry, biology, physics, geology, music, and art. Very impressive work!

The only downside was that we didn’t get a large enough audience. About eight parents attended, and maybe a dozen teachers or administrators, and (I would estimate) approximately 50 students in addition to the 60 participants, but we should have had more. There were several dozen students working in the library during the event, including some who had exhibited last year, some who have just been studying fractals in non-participating math classes, and some who will be studying fractals last year — but I was quite unsuccessful at persuading more than a handful to look at the posters and computer presentations. They were all too intently studying! I suppose that says something about Weston, but couldn’t they have taken 15 minutes out of their studying to see what their fellow students have accomplished?

On a related matter, I will also have to write a follow-up post about issues arising among competitive students when creating products in groups of two and three. But I first have to figure out what I can say in a public forum.

Labels: math, teaching and learning, Weston

Thursday, February 28, 2008

My 10 favorite books

Anyway, if you look at my profile (the link is near the upper-right corner of this blog), you will see the current list of my favorite books, in no particular order:

- A Pattern Language

- Getting Things Done

- Foundation

- A Clockwork Orange

- Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

- The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time

- Gödel, Escher, Bach

- How Children Fail

- The Odyssey

- The Nine Tailors

- The Lord of the Rings

- Excursions in Calculus

- The 1216-page A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction, by Christopher Alexander, is indeed about towns, buildings, and construction, as the subtitle claims, but it’s not just an architecture book or a city-planning book. This 1977 tome is all about the ways for us to design and think about the spaces we live in, written with a bit of a linguistic flavor as the title suggests. It truly helped me see the world differently, at least in terms of human interaction with our environment. Read it!

- I’ve already written twice before — in both 2006 and 2007 — about Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity, by David Allen (2001). See those links for more info concerning my thoughts on this valuable book.

- The classic Foundation series by Isaac Asimov is, well, a classic. But it’s so much more than that. It has had a major influence on science fiction fans, especially those (like me) who value historical points of view as well. Originally a trilogy formed out of eight short stories written from 1942 to 1950, it developed into a cluster of short stories and novels that altogether painted a sweeping view of future history. Though the series is not an example of elegantly written literature, its serviceably transparent style makes it worth reading multiple times, as I have done. The interaction between Asimov’s invented science of psychohistory and the discovery of chaos theory (which came after Asimov wrote the initial theory) is particularly intriguing for those who are interested in math. Try reading the series in the order suggested by the author.

- A Clockwork Orange, by Anthony Burgess, was a tour-de-force when published as a book in 1962 and subsequently as a movie released in 1971. It’s essential reading for two very different reasons: primarily because it is not written in English but in Nadsat, an invented teenage creole that combines Russian words with Cockney English; secondarily because it raises so many interesting questions about personal responsibility and decision-making.

- Mathematician Charles Dodgson’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1872), written (as everyone knows) under the pseudonym of Lewis Carroll, are not merely children’s novels but are masterpieces of language, logic, and a smidgen of mathematics. These two books are, of course, deeply embedded in our culture in so many ways, and are special favorites for those of us who love words and numbers. I especially recommend Martin Gardner’s Annotated Alice.

- The most recent book on this list is The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, a novel by Mark Haddon published in 2003. While the reader is initially attracted by the fact that the chapters are numbered 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, and 13 — and by the fact that the protagonist is a budding mathematician, the real interest in this novel is the author’s success in creating a first-person narrator with Asperger’s Syndrome.

- Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid is my #1 favorite book, so why is it listed seventh? This 1979 masterpiece by Douglas Hofstadter weaves together mathematics, computer science, art, and music around a central theme of recursion and self-reference. I’ve read it and reread it often, and have taught from it six or seven times. Gödel, Escher, Bach is an amazing book that has changed the way I think about so many things!

- In 1964, when I was halfway through high school and only beginning to think that I might become a teacher, I read John Holt’s newly written work, How Children Fail. Although the title sounds negative, it presages today’s emphasis on error analysis and differentiated instruction. I have read it several times, not only in high school and college but also after I began teaching, and I always recommend it to beginning teachers.

- By far the oldest book on this list is Homer’s Odyssey, definitely one of my top 10 — preferably in the original Greek but otherwise in the Robert Fitzgerald translation. I had the joy of reading much of this epic poem in Greek in eleventh grade and all of it in English in twelfth grade. I know, some people prefer the Iliad, but I’m definitely in the Odyssey camp.

- The Nine Tailors, by Dorothy Sayers, may or may not be my favorite mystery, but I guess it must be since it’s the only mystery on this list. Sayers’s elegant writing leads most people to place this 1934 novel in the literature category rather than the mystery category, and the lovely mathematics behind bell-ringing adds an extra charm for certain readers.

- I couldn’t leave out Tolkien’s famous 1937–1949 trilogy, The Lord of the Rings, which I’ve probably read eight or nine times. Everyone knows it, so there’s not much for me to say here other than that it’s the epitome of creating an imaginary garden with real toads in it. And I also surprised myself by loving the movie versions as well.

- Finally, last but certainly not least, comes the best math book in the world. Despite its title, Excursions in Calculus: An Interplay of the Continuous and the Discrete by Robert M. Young (1992), is not about calculus — at least most of it isn’t. The subtitle is more informative. This elegantly written work explores a wide variety of math problems in areas such as iteration, number theory, combinatorics, and algebra. Although there is plenty of exposition of the text, the real meat of the book comes in the hundreds of carefully chosen problems, many of which lead the reader to explore fresh topics in some depth. The catch? The “solutions” in the back of the book don’t actually provide any solutions; they merely tell the reader where to find the solutions. You will need an exceptionally well-equipped library in order to follow the links. Since I rarely am in such a library when I work through the problems, I have to cope with them on my own. I’ve twice used parts of Excursions in Calculus as a text for independent study by advanced high-school students; it works well for that purpose, but it also richly repays study by any math enthusiast at or above the first-year calculus level.

Labels: books

Wednesday, February 27, 2008

Thinking again about Obama/Bloomberg

More than 65 percent of Americans now live in urban areas — our nation’’ economic engines. But you would never know that listening to the presidential candidates. At a time when our national economy is sputtering, to say the least, what are we doing to fuel job growth in our cities, and to revive cities that have never fully recovered from the manufacturing losses of recent decades?Sounds to me like Obama. Sounds to me like a good match.

More of the same won’t do, on the economy or any other issue. We need innovative ideas, bold action and courageous leadership. That’s not just empty rhetoric, and the idea that we have the ability to solve our toughest problems isn’t some pie-in-the-sky dream. In New York, working with leaders from both parties and mayors and governors from across the country, we’ve demonstrated that an independent approach really can produce progress on the most critical issues, including the economy, education, the environment, energy, infrastructure and crime.

Labels: life

Tuesday, February 26, 2008

Nursery Crimes

“This is terrible. You don’t seem to understand. If Ruby doesn’t go to the right preschool, there is no way she’ll get into a decent elementary school. Then you can kiss high school good-bye. And let’s not discuss college. This is a crisis. An absolute crisis.”The characters in Nursery Crimes are mildly interesting, the satire is mild but amusing, the plot is mild but well-constructed. So “mild” does seem to be the operative word. Perhaps it’s unfair to observe that Waldman’s main claim to fame seems to be that she’s Michael Chabon’s wife, but that does seem to be how most people find out about her, even though their styles are so very different.

“She was impervious to my pleas, and seemed uninterested in my explanation of how not going to the right preschool would preclude Harvard, Swarthmore, or any other decent college. She’s end up at Slippery Rock State, like her dad.”

Labels: books

Monday, February 25, 2008

Curriculum B

With these four levels of granularity we tend to lose sight of the forest (to switch natural science metaphors), so we introduce other curricular concepts, like Big Ideas and Standards. For an example, see the Quadratic Functions unit in Weston’s Algebra II course, which lists eight Big Ideas spread out among four of our Standards. (Unlike concepts and skills, these terms require Capital Letters.)

But no matter what the level of granularity, all of this falls within what we might call Curriculum A. Math is what we know how to teach, and math is what we’ve been hired to teach, so math is what we do teach. In the old days math might have just been a laundry list of skills, but then we moved to higher and higher ways of thinking about it, from concepts through Big Ideas. Nevertheless, it’s just math. And if you pinned us down to analyzing what’s truly important, we would have to admit that there’s a hidden Curriculum B that’s more important than any particular mathematical skills or concepts or even Big Ideas. Why do we care so much about getting students to cite sources honestly, treat their classmates and teachers with respect, think creatively, question authority, work together cooperatively, and generally act like responsible adults? Because we know that in the long run those are what’s important. It sounds so fuzzy to claim that what we’re really teaching is honesty, respect for others, independent thinking, skepticism, cooperation, and responsibility, but surely there’s no doubt that those are more important than the quadratic formula.

Labels: math, teaching and learning, Weston

Sunday, February 24, 2008

If you can read this, you can read at a high-school level

After I wrote that paragraph, I wondered what the statistics are. In particular, what is the reading level of the average American adult? It turns out to be surprisingly difficult to get a valid answer. There is plenty of material giving figures (though inconsistent ones) about the shockingly large number of American adults who read at the third-grade level or below, who are unable to read a poison label, etc. In particular, Jonathan Kozol provides a wealth of material about functional illiteracy and its connections with race and class.

Labels: teaching and learning, technology

Saturday, February 23, 2008

Applying Yourself

I instantly understood that to adapt successfully meant to excel at classes, social life, and preprofessional development, all with minimal discernible effort. I thought I saw this being accomplished everywhere — by roommates, by friends on the Crimson, by classmates — and I could not understand why I was having so much trouble emulating their easy perfection. In my frustration I left unexamined the question of what I actually wanted, too concerned with my fears about keeping up with everyone else to care about understanding my own desires.

What surprises me now about how disconnected and inept I felt then was my absolute assumption that I was alone in my fears of inadequacy. Alone, I berated myself for getting caught up in destructive comparisons of myself to my peers, or for not knowing what I wanted to do after college, or for not getting a stellar grade. I worried occasionally that I was the only person I knew without a summer job lined up by November. I clammed up in sections, sure that my comments would be the least valuable of the discussion. Every small rejection or failure felt immeasurably personal, and it would have shocked me if someone had told me that other people had similar thoughts. Hiding my insecurities became almost another extracurricular activity, but one that nobody would put on a résumé.

Labels: Dorchester, life, teaching and learning, Weston

Friday, February 22, 2008

Sex vs. math

Students studying medicine are among those who have the most sexual partners compared to mathematicians who had the fewest.3σ→Left is quoting from the Daily Mail here. So probably these findings apply only to the UK, not to the US. Our teens can continue planning to become mathematicians. You think?

The results also revealed a range of activity according to subject choices. Almost half of all mathematicians have never had sex, whereas the average medic has had at least eight sexual partners. Cambridge University Students Union President Mark Fletcher seemed unsurprised by the findings. He said: “It’s obvious that the mathematicians haven’t found the winning formula yet. But it’s good to see that Doctors and Nurses is still a popular game.”

Thursday, February 21, 2008

Slay Ride

So now Grabenstein is 2–1 in my book. Let’s see what happens after I read Slay Ride. If I like it, we’ll declare him 3–1 and a general winner; if I don’t, we’ll have two series with two very different evaluations. So stay tuned...And now I have read Slay Ride. So, the envelope please. (Or is that the wrong metaphor? Do I mean, “Have you reached a verdict?”)

The answer, based now on four books, is that Grabenstein writes two series with two very different evaluations on my part. The Jersey Shore series (Tilt-A-Whirl and Mad Mouse) is fresh, entertaining, and well-written; the FBI series Slay Ride and Hell for the Holidays is adequate but depressing. Go read the first series — I’ll read other books in it — but don’t waste your time with the other.

Labels: books

Wednesday, February 20, 2008

Mozart and the Whale: The movie

The subtitle correctly prepares the viewer to expect two protagonists with Asperger’s Syndrome. But almost all the other characters as well were living with Asperger’s (or other forms of autism). And what I definitely hadn’t realized was that the movie is a semi-documentary, a fictionalized account of the lives of two real people: Jerry Newport and Mary Meinel-Newport. But even before I learned that, I knew that I had to see this movie, since some of my students have Asperger’s and since one of my ten favorite books is The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time. Definitely go see Mozart and the Whale for an unforgettable experience that is truly sympathetic without being at all sentimentalized!

What makes this a successful movie is the melding of the demands of fiction with the demands of a documentary. To meet the former, Norwegian director Petter Naess has emphasized a strongly traditional story arc with well-developed characters and plausible conflicts. To meet the latter, the film sets its diverse but self-aware characters firmly in the real world, with jobs and homes and even friends. The diversity is especially important, at least from my point of view. Over my career I’ve taught over a dozen students with Asperger’s, and I’ve worked with more than a few in the software industry; they all defy stereotypes, since no two are alike. The only aspect of the movie that rang a false note to my math-teacher’s mind was the inappropriate male-female ratio. In Mozart and the Whale almost half of those with Asperger’s are female, whereas in reality only 20–25% are. But Barbara reminds me that the movie does not show a random sample, but only those who volunteered to participate in a group; even among people with Asperger’s, society surely pushes females to be more sociable and more willing to participate in groups. (I’m dimly convinced that this is somehow related to the issues I discussed yesterday in my post about girls and math, but I haven’t yet worked out just how.)

You’ll have to see the movie to find out where the title comes from.

Labels: movies, teaching and learning

Tuesday, February 19, 2008

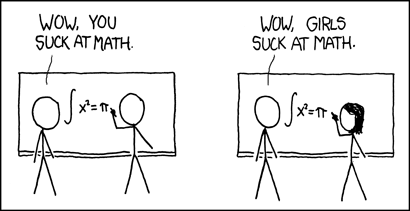

Girls can't do math.

The clueless guy on the left is a bit more blatant than most, but his view actually permeates our society — which is what makes the cartoon work. And in subtler ways it’s not just males who believe it. For instance, it’s easy to persuade boys to take BC Calculus, but girls often need convincing even when they’re among the top math students in their class.

A former student of mine who has been a math fanatic for years and is now a freshman at Wellesley writes about this problem in her “Math, Running, Fife & Drum, Education, Life...” blog:

All of my friends who are interested in math who are girls are very unconfident in their mathematical ability while the boys are confident... [T]hrough all my math experiences I’ve met mostly boys and few girls, most of the girls were also Asian (a different topic...) and most of the girls are not really interested in math but are more interested in science and math being a big part of science they also do math but in the future don’t have much interest in math. On the math team I have been on for the past two years there were 50 people each year and total I think about 70 people, at most 20 were girls, none of them have the same extreme interest in math as I do, though they enjoy math they could not imagine reading a math book for fun (something I do very often) or doing math in the future, when I suggest it most of them sort of laughed, most of them want to be pre-med...Do read the rest of Kelly’s post, as it provides a lot of interesting context surrounding this issue. (You will have to put up with the teenspeak style, although in Kelly’s case most of the writing is standard English.)

So I was curious about how the grades of my students correlate with their genders. My impression — before looking at data — is that while most of the very top math students are male, girls on the average do slightly better. (Again, we’re talking about grades, not about genuine interest in math.) So now let’s look at the data:

Last year’s final grades from my students show an average of 85.7 for boys and 83.1 for girls.Hmmm... apparently my hypothesis was half wrong. Most of the top students were indeed male, but males also earned higher averages overall than did females. This is a small sample, so I’m not sure that it really means anything. Still, it’s not what I had expected. Maybe the social pressures for girls not to do well in math extend more deeply than I had thought.

On a somewhat different but probably related matter, it’s worth noting that most teachers (both female and male) have a tendency to prefer teaching classes that are primarily female rather than classes that are primarily male. Although there are plenty of exceptions, girls are less likely to be behavior problems, more likely to take notes, and less likely to give the teacher a hard time. This is more just a matter of testosterone poisoning, as even very young boys tend to exhibit many of the negative characteristics of stereotypical male behavior. But the puzzle is how this interacts with achievement in math. If more girls than boys take their work seriously, do their homework, and cooperate with the teachers, why do fewer girls do well in math? Perhaps they just have different priorities.

Labels: math, teaching and learning, Weston

Monday, February 18, 2008

The Proper Ladies in Dorchester

Labels: Dorchester, life

Sunday, February 17, 2008

Model railroad show at the National Heritage Museum

It didn’t help that the adults at the show were outnumbered by the 4- and 5-year-olds. I suppose it’s nice to see that there are still young kids who are interested in model railroads — maybe there’s a future to the hobby after all — but it made it hard to concentrate. Actually, however, made it did help in the suspension-of-disbelief department, since the young kids tended to ooh and aah loudly about the trains and the bridges, not the quality of the representations, thus encouraging belief in the reality of the model. Otherwise the issue was the constraints imposed on modules that can be interchangeably connected mean that the total layout looked like what it was: a sequence of unrelated modules. There was no overall theme, no sense that this could be a real layout. Sure, a canyon or a truss bridge or an industrial area might look authentic, but it’s not part of an authentic whole. It all reminds me of the typical Algebra II course, which consists of several vaguely related modules instead of a unifying theme — in other words, instead of a course. A model railroad should reflect some consistent big ideas; it shouldn’t just be independent modules that happen to meet at each end.

Labels: model railroads

Saturday, February 16, 2008

Ivy Restaurant

Ivy positions itself as a good spot for today’s diner with moderately priced wine and lots of small plates. The fare by chef Joshua Breen can be inconsistent at times, but when he’s on, Italian comfort food fits the niche with aplomb.Fair enough — a bit vague, but not incorrect.

And then we have Robert Nadeau’s review in the Boston Phoenix. Here are some excerpts:

Small plates could serve as appetizers or a snack, or two could be a meal for many people. Pasta plates were the size you get in Italy. Gnocchi Sorrentina ($11) were dense pasta nuts with a spicy tomato sauce. Tiger-shrimp linguine ($12) was not as al dente as it would have been in Italy, but it was nicely flavored, with just-wilted arugula and very tender shrimp.Now this review is a year and a half old (and maybe the Globe review is of a similar vintage); some things have changed since then. There are a couple of ways in which the review is significantly out-of-date: in particular, there is now only one real entrée, so the only plausible way to assemble a dinner is to have a combination of small plates, either individually or shared; there is also a dessert now. The “large stemware” may show the wines well, but Barbara is quite unhappy with this new trend. Both Ivy and dBar told us that the huge, unwieldy glasses (each of which could hold almost a full bottle of wine) were the only ones they had. Apparently ridiculously large glasses are the new black; Barbara blames Ming Tsai.

On the protein tip, duck confit ($12) was a small, nicely cured leg (though not with spices), and a side salad of arugula. Mussels ($9) were a fine little heap, reasonably plump for the season, with a good dipping sauce with plenty of garlic and pepper. Tuna ($12) was sushi-quality slices, seared on one side and crusted with black and white sesame seeds. The dip was the kind of pink-mayonnaise hot sauce you get in the hotter sushi places. There was also a tiny side salad of shredded cucumber and a bit of dill. Scallops ($12) were three tasty sea scallops with a lot of pancetta (which now seems to include smoked bacon on Italian menus) and a wisp of sauce.

There are also side dishes, such as herbed frites ($5), which weren’t herbed or crisp, but did have a lot of potato flavor, served in a paper bag on a fancy plate. Grilled asparagus ($5) were nicely done, but with the sub-pencil-thin asparagus available in August: kind of chewy. This is the time of year when you should put in something like grilled zucchini instead.

There are only four real entrées, and at least three are excellent...

The wine policy at Ivy is to maintain a long list, mostly Italian, but with others from around the world to fill in, all at the same price: $26 per bottle, $10 for a six-ounce glass, $18 for a 12-ounce “Quartino.” The stemware is large, so the wines will show well...

Ivy does not have desserts. This is a reasonable policy for a restaurant whose dinner business may prove to be mostly pre-theater, and which wants lounge and small-plate customers for most of the evening...

Service at Ivy was quite good. We asked for our dishes as they came from the kitchen, and our server didn’t seem to mind the extra trips involved. The atmosphere is still somewhat in limbo, as one feels odd eating a full-course meal in a lounge, even when seated at a table with a tablecloth (or one marble-topped larger table in back). The music is some kind of background electronica — a sample CD was sent as part of the promotion for the opening of the restaurant. The crowd looks young and bar-friendly, but not crowded or trendy. The division into small rooms keeps down some of the noise.

The décor is rather darker than Limbo’s was, with an interesting new motif of black-iron fences on the walls — the kind of fences that surrounded Victorian homes. There is still some bare brick, red lights, fun and mismatched lamps and chandeliers, and a variety of seating situations.

Anyway, the black-iron fences on the walls are totally cool, the music is too loud, and it is indeed true that “the crowd looks young and bar-friendly, but not crowded or trendy. The division into small rooms keeps down some of the noise.” Although Ivy clearly appeals mostly to 30-somethings, we certainly weren’t the only older diners and didn’t feel out of place.

Oh — what about the food, you ask? Barbara and I ordered four small plates: adequate arancini to share (we asked for the variety with prosciutto, but the waitress seems to have brought us the version with truffles instead); steak frites for Barbara (cooked to medium rare as requested, with excellent frites, which the chef made reasonably crispy unlike Nadeau’s experience); excellent medium-rare pork loin with figs, cherries, and apples for me; and grilled asparagus for us to share. Since this is February rather than August, I can’t compare our asparagus with his — but ours were wonderful. For dessert I ate half of a portion of ricotta pie, which came from some bakery in the North End whose name I forget; it was too large and too sweet, but otherwise it was delicious, including a yummy dark chocolate center.

So, what was the bottom line? It all came to a hundred dollars less than dBar, even with the tax, tip, a couple of after-dinner drinks, and the famous fixed-price bottle of wine (a very good Two Brothers Big Tattoo Red in our case). Perfectly reasonable, even though we had been looking for something even less expensive to balance out the pricey theatre tickets.

Ivy wouldn’t be near the top of our list, but we would definitely return when we’re in the neighborhood.

Labels: food

Friday, February 15, 2008

dBar

There was, of course, a special menu for Valentine’s Day; it featured a four-course prix-fixe dinner. The first course was a delicious amuse-bouche misleadingly labeled “beet ravioli”; it turned out that no pasta was harmed involved in the making of this dish, which consisted of three thin pairs of heart-shaped pieces cut from beets, with goat cheese and herbs in the middle of each pair. The second course offered a choice of several appetizers; Barbara had a huge sea scallop with various greens, and I had carpaccio with accompaniments. The third course offered half a dozen entrées; Barbara had sea bass, and I had “duck, duck, goose,” which consisted of a duck breast cooked medium rare, a duck leg cooked until falling off the bone, and a tiny piece of goose pate. The fourth course offered a choice of two desserts; we each had a flourless chocolate cake accompanied by a strawberry dipped in chocolate and whipped cream.

Service was excellent, being attentive without excessive hovering. They were particularly good at responding to my tree-nut allergy: the “beet ravioli” were made with walnuts mixed into the goat cheese, but the chef had prepared one nut-free set for me ahead of time because our reservation had mentioned my allergy. Likewise, the duck was supposed to include pistachios in the sauce, and I’m sure that they would have remember to omit them from my order even if I hadn’t reminded the waiter.

What with a double espresso and a fairly reasonable bottle of wine, it all came to about $230 after tax and tip. Ouch! But worth it.

Labels: Dorchester, food

Thursday, February 14, 2008

My Fair Lady

Although it has been 26 years since the last time I saw My Fair Lady, I still know it practically by heart, since it’s unquestionably my favorite musical ever. So I was intrigued by some of the changes from the classic productions of the original cast and the movie. In particular, the director turned “With a Little Bit of Luck” into a highly entertaining production number, “Show Me” into attendance by Eliza at a suffragette rally, and the Ascot scene into mourning for King Edward VII (the date of the action was moved from 1912 to 1910). All of these amounted to a lagniappe for the audience — enhancing the original conception of this musical rather than destroying it.

I’ve been told that the reason I like My Fair Lady so much might be that I have a background in linguistics, but I’m not at all sure that that’s it. Yes, the linguistic aspects of the musical certainly add extra meaning and interest for me, but they certainly aren’t the main theme of the show. Besides, I loved My Fair Lady before I became a linguist. Actually, I’m more intrigued by its meaning to me as a teacher. Or should I be referring to Shaw’s Pygmalion, on which most of My Fair Lady (except for the unfortunate last scene) is very closely based? The Greek myth of Pygmalion is always a cautionary tale for teachers, since we run the risk of taking credit for our students’ achievements — and, by extension, blame for their failures. The entire way that Professor Henry Higgins thinks of Eliza as his personal creation is all too tempting, especially in the current political climate in which teachers are supposed to be “accountable” for what their students do. I’m not going to get on the subject of merit pay now while reviewing a play, but it’s surprisingly relevant. More on this later, perhaps.

Before the show we had dinner at Ivy; I’ll post a review in a couple of days.

Labels: life, linguistics

Wednesday, February 13, 2008

A calculator that promotes understanding

My first impression was that they had stolen our idea! If you compare the description from TI with the Weston Math Department’s multiple-representation worksheet, you see a remarkable resemblance. Then again, maybe it’s not so remarkable. Consider what TI says on its webpage:

New TI-Nspire technology was developed hand-in-hand with educators worldwide... TI-Nspire technology empowers students to learn across different visual representations of a problem, developing a deeper understanding of mathematical concepts. When students can see the math in different ways, they are able to broaden their critical thinking skills and discover meaningful real-world connections.Yes, it sounds just like something my Weston colleagues and I would write, but I guess that’s not a coincidence if the device truly was developed “hand-in-hand with educators worldwide.”

So, what’s so exciting? Well, here’s why it sounds so great: Apparently (if we believe the ads) the TI-Nspire provides multiple representations on a single screen — such as a dynamic geometric image, a table, an equation, and a graph — and changing one representation makes corresponding changes in the others. If this capability really works as advertised, it should indeed help promote deeper understanding. I’m looking forward to exploring the implications of this tool for our curriculum. It might be the catalyst for significant changes in teaching and learning.

Labels: math, teaching and learning, Weston

Tuesday, February 12, 2008

Post #500!

I can’t speak for anyone else, but the truth is that I often feel impelled to share my thoughts with others, and blogging is a good way to do so. It’s not the main reason I became a teacher — that’s more a matter of my interest in seeing people learn and helping them do so — but it’s surely a secondary reason, both for me and for many other teachers. For my entire teaching career I have wanted people to become better thinkers and better problem-solvers, so I want to help lead them in what I see as the right directions. Those people might be my students (in Weston, at The Saturday Course, at the Crimson Summer Academy), or they might be my colleagues or the general public. Blogging is just one of the ways I can reach them. I’m pleased to have kept it up for 500 posts, and I’m looking forward to 500 more.

Labels: life, technology, Weston

Monday, February 11, 2008

Two Weston students think about poverty

The first was a conversation between two ninth-graders in the Math Office. It was held in my presence, but they were clearly talking to each other, not to me. One student was complaining about her parents’ values. “When I grow up, I’m not gonna live in a rich town like Weston. I don’t care about material possessions the way my mom and dad do. I don’t need to have a big house and a big car. I’m gonna live in a poor community.”

“You mean like Waltham?” asked the second freshman.

“Certainly not!” replied the first student in a tone of horror. “I wouldn’t want to live anywhere that’s that poor!”

The second incident occurred a couple of days ago when a sophomore came into her math class in a huff. Apparently her English class had just been discussing poverty in Compton, California — I don’t know what book they were reading, but there are several possibilities under the circumstances. My student was incensed by one of her classmates, who had actually said this:

Why do the people in Compton think they have it so tough? Life is actually much harder for us in Weston. We have all this pressure to get good grades and get into the top colleges; they don’t have that kind of stress in Compton!I just don’t know what to say. Usually we think that the purpose of the METCO program is to “expand educational opportunities” for minority students from Dorchester and Roxbury, but maybe its main purpose is to bring the real world to white students who live all their days in the isolated, rich suburbs.

Sunday, February 10, 2008

The Globe corrects a small error about Dorchester

Because of a reporting error, a Jan. 27 story on the Paul Revere House incorrectly identified the North End building as the oldest house in Boston. Dating to about 1661, the Blake House in Dorchester is the oldest, according to the Dorchester Historical SocietyAs far as slights to Dorchester go, this is of course small potatoes, but it’s still nice to see the Globe’s recognition of something positive about the part of Boston where they are located. We’ll take our victories where we can get them, no matter how minor.

Labels: Dorchester

Friday, February 08, 2008

Is Prisoner's Dilemma still teachable?

Tanya and Cinque have been arrested for robbing the Hibernia Savings Bank and placed in separate isolation cells. Both care much more about their personal freedom than about the welfare of their accomplice. A clever prosecutor makes the following offer to each. “You may choose to confess or remain silent. If you confess and your accomplice remains silent I will drop all charges against you and use your testimony to ensure that your accomplice does serious time. Likewise, if your accomplice confesses while you remain silent, they will go free while you do the time. If you both confess I get two convictions, but I’ll see to it that you both get early parole. If you both remain silent, I’ll have to settle for token sentences on firearms possession charges. If you wish to confess, you must leave a note with the jailer before my return tomorrow morning.”You can see why it is indeed a dilemma. If each prisoner acts rationally (as the economists would put it), each must confess (or defect, in the language of game theory). But both would be better off if both remain silent (or cooperate with each other, in the language of game theory)!

The “dilemma” faced by the prisoners here is that, whatever the other does, each is better off confessing than remaining silent. But the outcome obtained when both confess is worse for each than the outcome they would have obtained had both remained silent. A common view is that the puzzle illustrates a conflict between individual and group rationality.

This used to be easy to teach. First the class discusses the problem and does the mathematics in order to understand the four options, usually presented in a 2-by-2 table (the row prisoner can cooperate or defect, the column prisoner can cooperate or defect). This is known as a simultaneous game, since neither party knows the other’s decision before making their own decision. I’ve taught this problem to a truly wide variety of classes, ranging from fifth-graders to high-school students to adults, from inner-city kids to wealthy suburbanites, and in past years the outcome was almost always the same: approximately two-thirds would choose to defect, thereby ensuring a non-optimal outcome. After further discussion of the mathematics, a few defectors would choose to cooperate, but a few cooperators would choose to defect, on the (rational) grounds that they couldn’t afford to trust the other guy. After all, no matter what the other guy does, you are indisputably better off if you defect.

But the situation has changed in recent years. Because of the infection of the “don’t snitch” ethic in our society, the vote is now overwhelming in favor of cooperating, especially among inner-city kids. No matter how much you tell them to treat it as a math problem, no matter how much you add conditions like “your accomplice has no powerful friends and can’t go after you,” people are unwilling to defect. The problem becomes unteachable. In the students’ eyes it’s no longer a dilemma.

There seem to be two solutions to this difficulty if one still believes that the Prisoner’s Dilemma provides important fodder for discussing ethical and political decisions. One solution is to modify the payoffs so that they are positive rather than negative, thereby removing the story from the realm of crime to some other less charged realm. Another possibility is to change the context so that defecting doesn’t consist of “snitching.” I’m working on it. I’ll figure out a plan before I need to teach the problem again this summer at the Crimson Summer Academy, where it forms the Big Question for half of the eleventh-grade portion of the Quantitative Reasoning course.

Labels: Dorchester, life, math, teaching and learning, Weston

Wednesday, February 06, 2008

Maybe Yelp knows...finally...that Dorchester is part of Boston

The neighborhood of Dorchester’s hip establishments are rapidly growing, but you wouldn’t even know it was part of Boston if you regularly go to the popular user review website Yelp (www.yelp.com/boston) because it is not listed as so. After several attempts to contact Yelp about this, including a response telling us they are “working on it”, nothing has been done.OK, so I followed their advice and actually sent two slightly different comments to Yelp: one to their San Francisco headquarters that assumed that they didn’t know that Dot is part of Boston, and one to their Boston office that assumed that of course they knew but had just accidentally overlooked it.

This omission seems almost purposeful. Several neighborhoods of the city that offer far fewer resturants and shops than Dorchester are listed (including Dudley Square, Egleston Square, Mission Hill, South Boston, Hyde Park, etc.). On top of this, many places that are not even in Boston are listed as neighborhoods of the city, including Central and Harvard Squares (in the city of Cambridge), Coolidge Corner (in the town of Brookline), Davis Square (in the city of Somerville), Arlington Center (in the town of Arlington), and Winthrop (which is a separate town in itself), etc.

We are asking our readers to take a moment and send a comment to Yelp that Dorchester needs to be added to their list of Boston neighborhoods. This simple action will encourage more people in the city to visit Dot (because Yelp is such a widely used website by people under 40), having a positive effect on our local businesses.

Then the effort heated up a bit when Adam Gaffin picked up Chris and Erin’s remarks and linked to them in Universal Hub later that same day, with an appropriate headline observing “Yet Another Online Guide that Ignores Half the City” (Yelp also ignores Roslindale and Mattapan in addition to Dorchester). I don’t know whether that made any difference to Yelp, but I was pleased to receive prompt responses from them. First of all, a few hours later (still on the same day), one Ligaya Tichy from the local Boston office wrote back to me:

Thanks for writing in. We’re on it! We currently have listings including businesses in Dorchester but we will be adding it as a neighborhood in the next few. Keep an eye out, and have a great weekend!And then I received this message today from Stacy No-Last-Name at Yelp’s SF headquarters:

Thanks for contacting Yelp and for letting us know about our oversight. We’re in the process of getting that information updated as quickly as possible.So, now we just have to see what actually happens, if anything. As I said in my previous post, but in an entirely different context, stay tuned...

See you on Yelp!

Labels: Dorchester

Monday, February 04, 2008

Mad Mouse

I am pleased to report that I loved Mad Mouse, primarily because it was so much fun to read. As I was reading, I kept saying to myself, “Grabenstein obviously enjoyed writing this!” And I, likewise, enjoyed reading it. The characters are funny, but never annoyingly so; the setting on the Jersey Shore is convincing; and the plot moves quickly in an engaging way, being complex enough to be interesting but simple enough to be followed without excessive effort.

OK, so it’s not serious literature. But it’s exciting and amusing, a great way to take one’s mind off the stresses of dealing with teaching mathematics to teens (rich and otherwise) all day.

So now Grabenstein is 2–1 in my book. Let’s see what happens after I read Slay Ride. If I like it, we’ll declare him 3–1 and a general winner; if I don’t, we’ll have two series with two very different evaluations. So stay tuned...

Labels: books

Saturday, February 02, 2008

The Beautiful Miscellaneous

Yes, it’s an interesting and well-written novel about fathers and sons, about coming of age, and about giftedness or the lack thereof. So what left me unsatisfied? Maybe I was irritated by the intrusion of so-called psychics into the world of physics and mathematics. Maybe I was bothered by the intrusiveness of synesthesia and photographic memory into what was otherwise a straight novel. While I was definitely affected by my reading of A.R. Luria’s The Mind of a Mnemonist as an undergraduate, it doesn’t make the most convincing fit in a fictional context. Or maybe I’m just being unfair and wanted the book to be something it wasn’t. In any case, I certainly don’t feel that listening to The Beautiful Miscellaneous was a waste of time, so give it a read — or a listen.

Labels: books

Friday, February 01, 2008

When am I ever going to use this stuff?

Sometimes the question comes from a bored student who is really asking a deeper question, something like, “I don’t like this, I don’t understand this, why should I have to learn it?” In that case it’s hard to know whether to answer the explicit question or the implicit question.

But sometimes the question comes from an otherwise engaged student who actually wants an answer. And it’s hard to give a satisfactory answer. There are at least two reasons for this — probably more. First of all, no high-school student really knows what he or she is going to be doing in life. It’s important to keep the doors open, in case the unanticipated economics course in college or statistical analysis in a job turns out to require something from a high-school math course. But that’s pretty vague and abstract, and of course it isn’t a very satisfactory answer for most students, even though it’s a true answer.

The other reason why the question is hard to answer is that the hidden but more important curriculum in high school has nothing to do with the specifics of logarithms, cosines, etc. When a student takes Algebra II or Precalculus or whatever, the important things that s/he is learning have to do with problem solving, approaches to mathematics, and learning itself. Sure, you might never see logs again (although the odds are that you actually will); but the analytic techniques and reasoning methods that you learn will stand you in good stead.

The only trouble is that most Weston students don’t want to hear this, or it doesn’t make sense to them. They want to know how they are going to use the precise content in the job that they imagine that they will have, even though the probability is that they will be doing something else entirely. How do we give them an answer that they will consider satisfactory?

Labels: math, teaching and learning, Weston

ARCHIVES

- May 2005

- June 2005

- July 2005

- August 2005

- September 2005

- October 2005

- November 2005

- December 2005

- January 2006

- February 2006

- March 2006

- April 2006

- May 2006

- August 2006

- September 2006

- November 2006

- December 2006

- January 2007

- February 2007

- March 2007

- April 2007

- May 2007

- December 2007

- January 2008

- February 2008

- March 2008

- April 2008

- May 2008

- July 2008

- November 2008

- December 2008

- January 2009